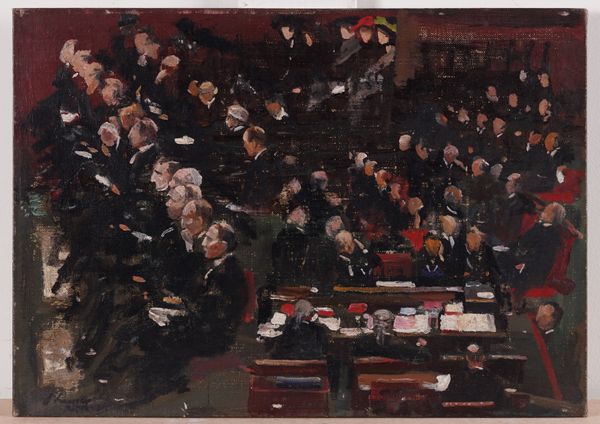

SIR JOHN LAVERY (IRISH, 1856-1941)

Study for ‘The Ratification of the Irish Treaty in the House of Lords, December 1921’

signed 'J Lavery' (lower left), inscribed 'HOUSE OF LORDS STUDY/ LAVERY' (on the backboard)

oil on canvas-board

25 x 35cm

Provenance

Property of the Artist;

Gifted by Lavery to the sculptor, George Henry Paulin (1888-1962), circa 1934;

Gifted by his wife, Muriel Margaret Cairns, to her son-in-law as a wedding present on 15th March 1969;

Thence by descent to the present owner

| Estimate: | £20,000 - £30,000 |

| Hammer price: | £35,000 |

Catalogue Note

Arguably, 16 December 1921 is one of the most auspicious dates in British history. On that

Friday, the Irish Treaty passed from the Commons to the House of Lords for ratification.

From that moment the British Empire, which had been expanding rapidly since the 1870s,

went into steep decline, and civil war in Ireland, watched by Gandhi and others, led to the

emergence of a ‘Free State’. The eyewitness on this portentous occasion was Sir John

Lavery.

He arrived well prepared. Taking his seat in the centre of the Strangers’ Gallery, directly

facing the thrones, he had come equipped with a ‘pochade’ box, and an ample supply of 10 x

14-inch canvas-boards, primed in burnt umber (1).

Now in his mid-sixties, Lavery’s illustrious career began over thirty years earlier when, as a

Paris Salon medallist, he was commissioned to paint The State Visit of Queen Victoria to the

International Exhibition, Glasgow, 1888 (Glasgow Museums). One of the first featured

artists at the Venice Biennale and an Academician, he had been knighted for his services as

an Official War Artist. Although known as a portrait painter, Lavery was also renowned for

his ability to capture the specific newsworthy occasion. That early royal reception in

Glasgow lasted no more than 30 minutes, but his job was not only to record the scene, but

also to portray each of its 254 participants – a task that took two years to complete.

Something of the same challenge lay before him in December 1921 when Earl Morley rose in

the Lords to present the Irish Treaty Bill. Lavery could not know in advance how long he

would have, so he must work quickly, roving his eye to either side of the house, catching

profiles from the seated members. These vital jottings were not composed as pictures; they

were fragments to be brought together in the studio.

In the present work, a recently rediscovered missing link in the series, the artist catches

the heads of three women spectators in the Strangers’ Gallery, dropping to two series of

members’ rows taking us down to the floor of the house and what may be the head of Morley

– a mere dab of flesh colour. Then in the foreground, directly beneath where he was sitting,

we see the barristers’ desk with its litter of papers, facing the Lord Speaker’s and Judges’

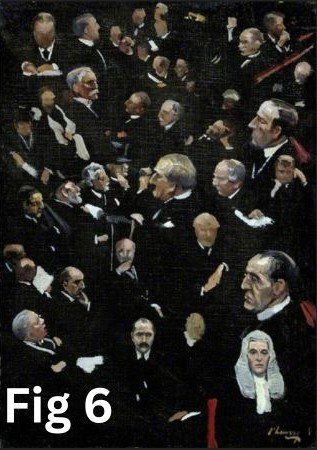

woolsacks (2). Other canvas-boards produced in the same few minutes show rows on the left of

the house and more prominent identifiable heads (fig 6) (3).

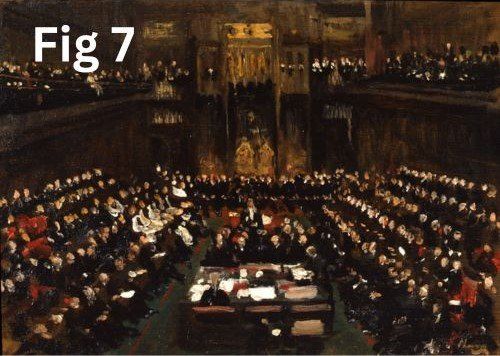

Two ensemble sketches also form part of the series, one revealing the full range of benches to

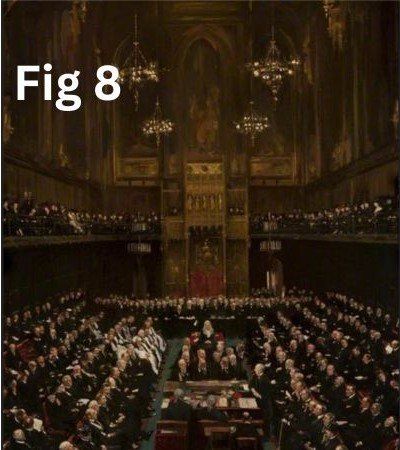

left and right (fig 7), and the other, the full height of the chamber – as would be seen in the

final composition (4). With these in hand Lavery started work immediately on the large version

which was to be his principal exhibit at the Royal Academy the following year, hailed in one

newspaper as examples of ‘that most difficult branch of art, the painting of contemporary

history’ (fig 8) (5).

Although tempted to file away, paint over or otherwise discard his working notes, Lavery

seldom did so. When giving one to Sir Ian Hamilton for instance he told him that this was the

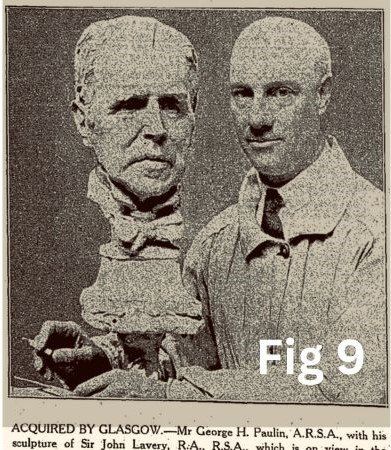

first oil painting of the House in session, adding that it was thus, an ‘historical document’ (6). This was to be the case a dozen years later when the present sketch was retrieved from the

racks for George Henry Paulin ARSA (1888-1962) in gratitude for his fine portrait of Lavery,

a cast of which can be found in Glasgow Museums (fig 9) (7).

Prized for their authenticity as ‘historical documents’, Lavery’s on-the-spot sketches do not

neglect the aesthetic potential of what lay before his eyes. As in the present case, collaged

and disconnected vignettes are set down with remarkable spontaneity. They are neither

snapshots nor newsreel. No nearby gossip nor sudden crash would distract him. Throughout

his career observers, those looking over his shoulder as he worked, commented upon his

formidable concentration as the action rolled out before his eyes. He kept pace with its

unfolding even in the most testing of circumstances. Mastery is avid of complications. He

was trained for this.

Bellmans are extremely grateful to Professor Kenneth McConkey for this catalogue note.

Footnotes

1. Lavery had sought the assistance of Sir Patrick Ford and Lord Birkenhead in obtaining permission to

paint while the House was in session; see John Lavery, The Life of a Painter, 1940, (Cassel), p. 186-7.

2. Lord Curzon, the Lord Speaker, during these years was acting as Foreign Secretary, but frozen out of

the Peace Treaty negotiations at Versailles by Lloyd George, frequently passed his duties to his friend, FE

Smith, Lord Birkenhead.

3. Two other identifiable sketches are known (both private collections), one naming the chief actors –

Carson, Birkenhead etc.

4. The upright sketch is contained in the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin.

5. Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 5 May 1922, p. 6.

6. Quoted in Kenneth McConkey, John Lavery, A Painter and his World, 2010 (Atelier Books,

Edinburgh), p. 236 (note 37). Lavery frequently gave sketches like these as souvenirs to friends and sitters.

Lavery’s own views on Irish independence were clearly declared in a letter to his friend and pupil, Winston

Churchill, then Minister for the Colonies. He wrote that he believed that Ireland ‘…will never be ruled by

Westminster, the Vatican, or Ulster, without continuous bloodshed … and [that] leaving Irishmen to settle their

own affairs is the only solution’ (McConkey 2010, p. 154).

7. Paulin’s sculpture was currently on exhibition at the Royal Glasgow Institute of the Fine Arts in

October 1934 (no 4) and the cast was acquired by Glasgow Museums at this time. The work (possibly a further

cast) was then exhibited with a series of artists’ portraits in Paulin’s exhibition at the Walker Galleries, London,

in June 1935.

Condition Report

The canvas-board is sound; paint surface in good original condition; minor frame abrasions to outer edges, only visible upon examination out of frame; ultraviolet reveals an even varnish but no sign of retouching - good, original condition; under glass and held in a gilt-painted wooden frame in fair condition.